Since the tragic death of George Floyd in America in May 2020, and the Black Lives Matter protests against racism, Bath Abbey has pledged to address its history, learn from it and help others to do so too. The following information is from a 2021 exhibition which was held to show our commitment to starting this process.

Monuments, Empire and Slavery

Welcome to this exhibition. We wish to God that it were not needed.

Slavery should have no place in society, and must be renounced utterly. It is shameful that it was practised for so long, without effective challenge by church or nation.

At Bath Abbey we deeply regret the hateful industry of human exploitation, whether by ignorant complicity or evil design, testified by certain of our memorials from the 1700s and 1800s.

‘Monuments, Empire and Slavery’ seeks to expose that guilty heritage, and to help learn from it.

Along with the whole Church of England, we apologise unreservedly for having condoned or sustained transatlantic slavery, in any way whatever. We give thanks for the Christian legacy of William Wilberforce, and all forebears who fought instead, long and hard, for abolition of the slave trade.

Sadly of course, the fight is not yet over. Human exploitation and racial prejudice, most emphatically, are not just in the past. As you visit, please pray with us, that we may be challenged “From Lament to Action*” in our own day. Thank-you.

Guy Bridgewater

Rector of Bath Abbey

* 'From Lament to Action' is the title of significant proposals, facing up to racism in the Church of England (published March 2021). For the Church’s battle against modern slavery, please see the Clewer Initiative.

Monuments, the British Empire, and Slavery

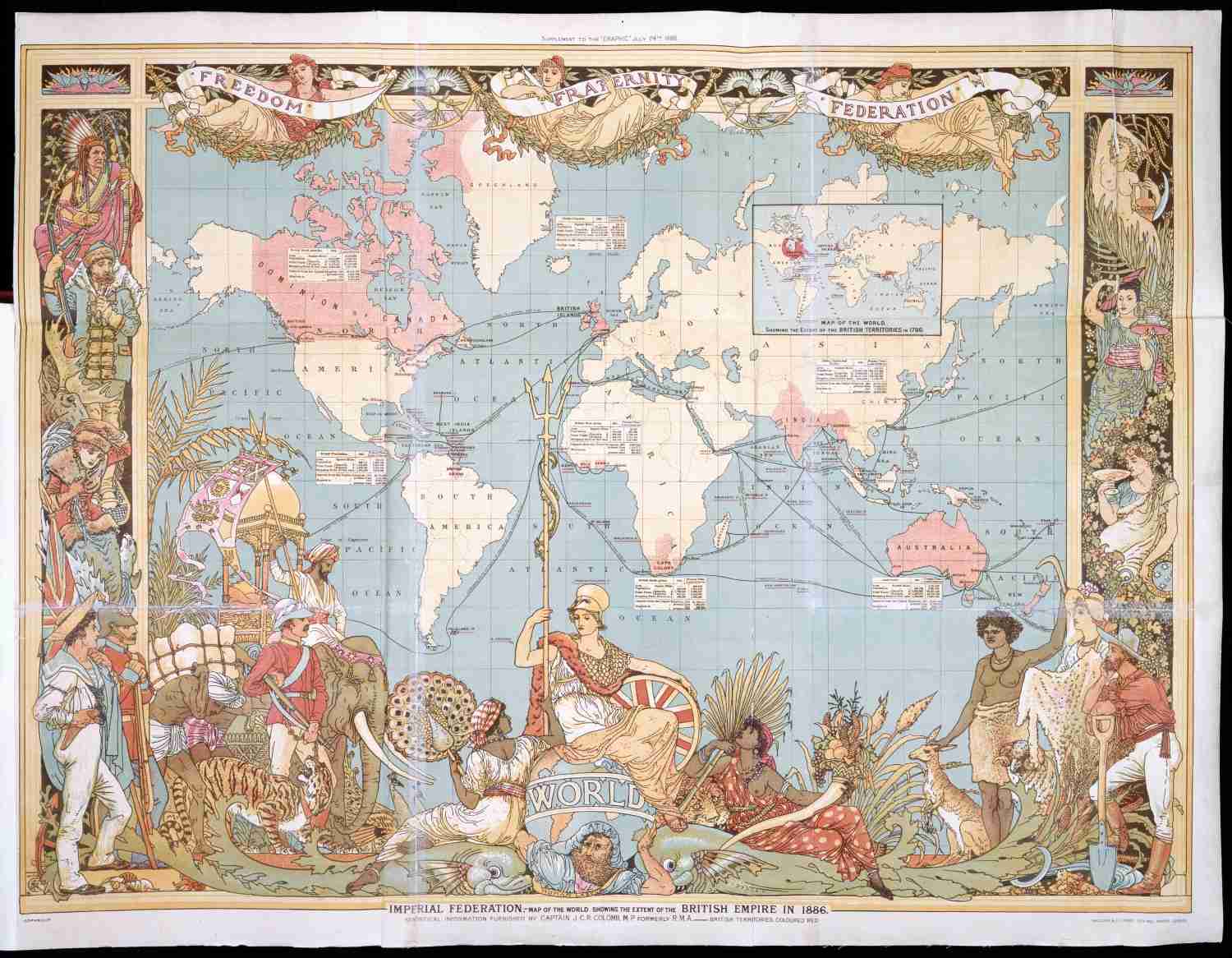

The red areas in the map show the size of the British Empire by 1886 - about 25% of the world's land surface.

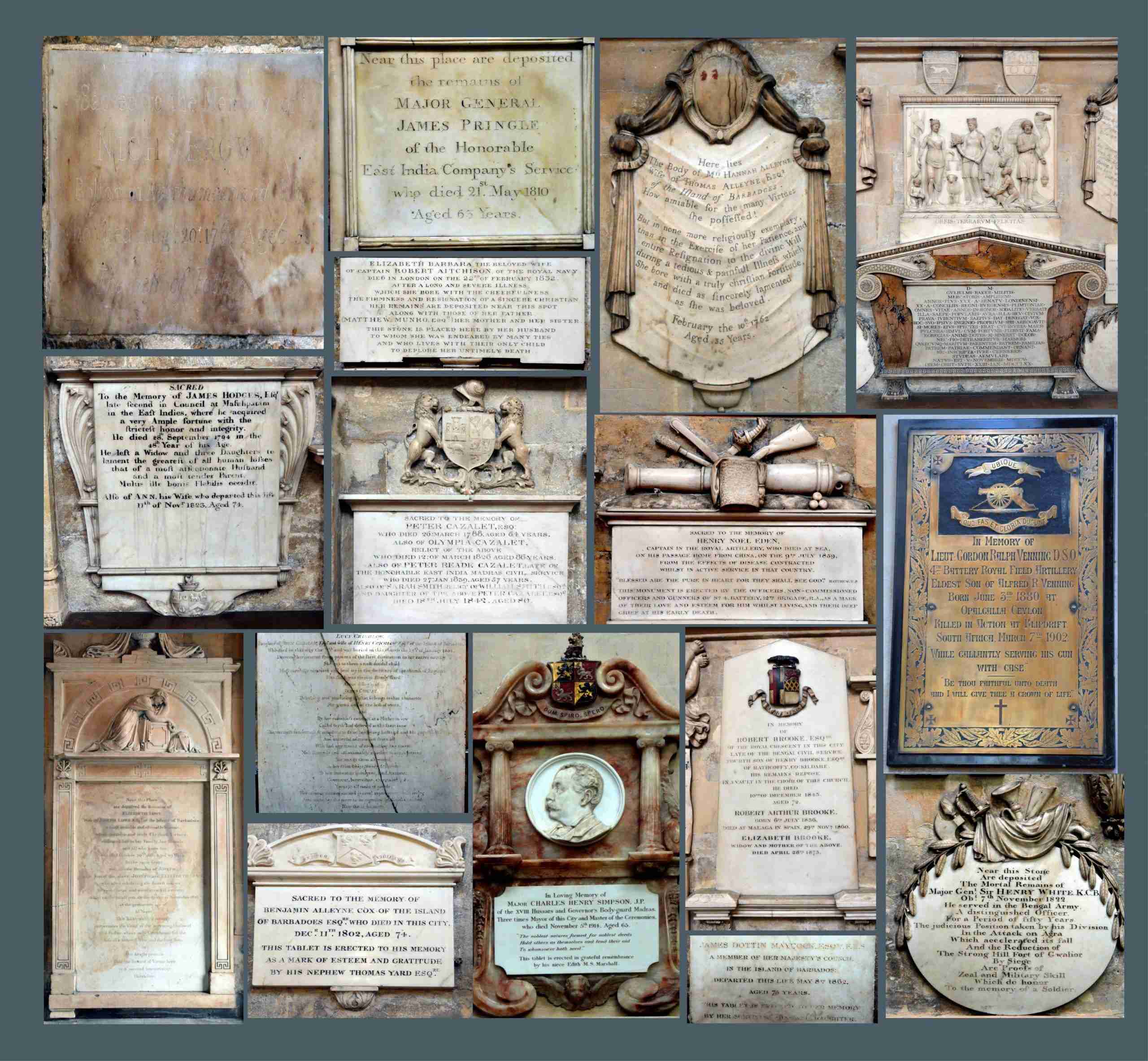

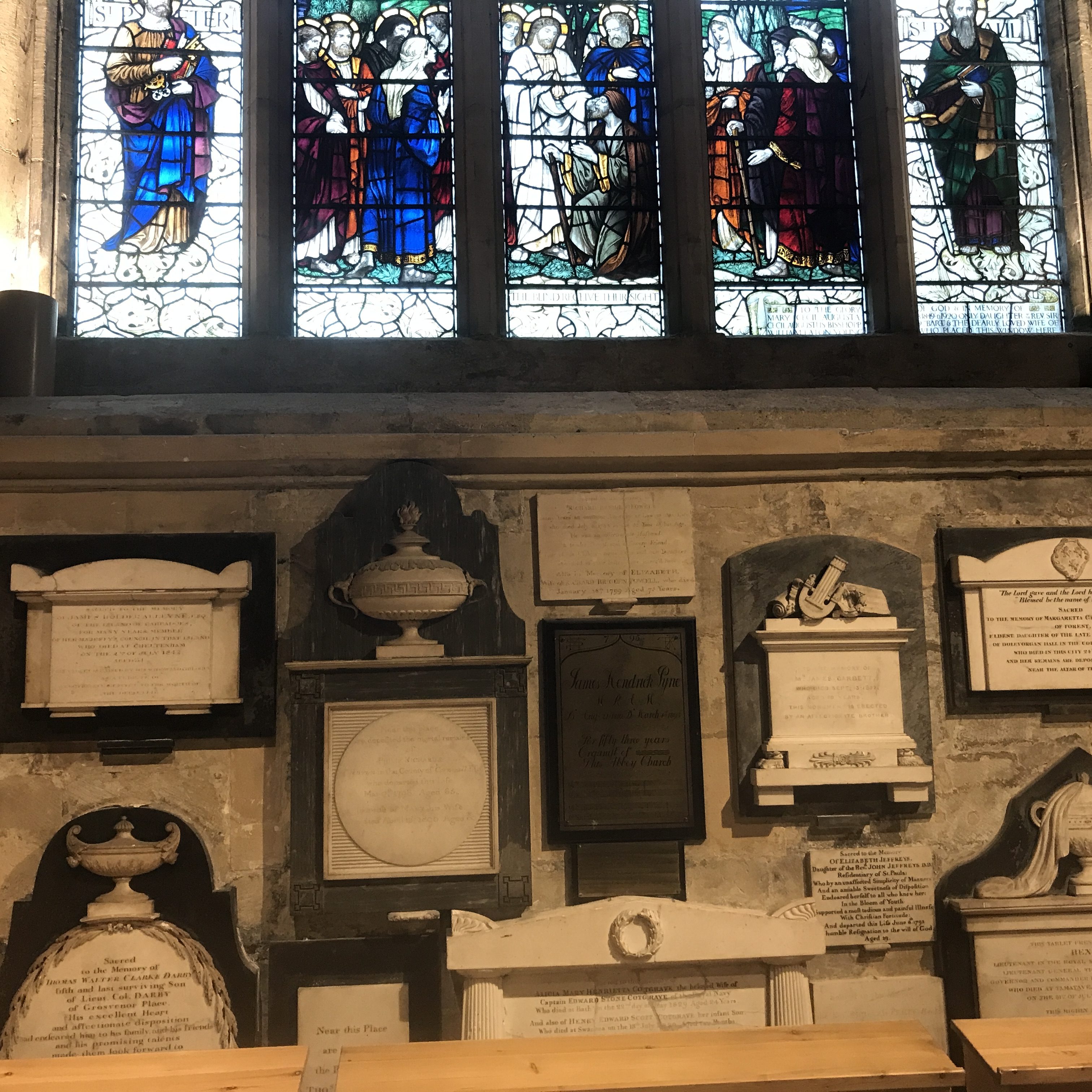

Between 1572–1845, 891 ledgerstones (gravestones) and 635 wall tablets were erected in Bath Abbey. They commemorate 1,455 of the approximately 7,000 people buried in the church and only those from the middle-to-upper classes. In the same period, Britain established an empire by creating colonies (seizing control of lands and peoples across the world). Those with a monument here are therefore often connected to that exploitation.

Bath Abbey benefited from the British Empire in as much as it accepted payments for monuments from the families of those involved in it. The monuments commemorate those who governed and administrated the empire, like Sir William Baker, those who expanded and protected the empire, like Captain Bartholomew Stibbs, and those who owned and sold the empire’s produce, like the sugar plantation owning Alleyne and Maycock families.

The British Empire seen through our Monuments

On the wall of the South Aisle is a monument to Sir William Baker (1705-1770). As a Director of the East India Company (1741-1753) and Governor of the Hudson Bay Company (1760-1770) he oversaw two of the most powerful companies which helped to establish the British Empire's colonies in India and Canada in the 1700s.

His monument shows a female representing London (Baker's birthplace) at the very centre of the empire. She holds a cornucopia (a horn overflowing with exotic fruits and flowers) and stands above the others, receiving textiles, ivory, and incense from a turbaned man and a beaver (representing the fur trade) from a naked, indigenous Canadian. The monument's text praises Baker as "the father of his country". The monuments here often idealise and celebrate the Empire and those involved in it.

"It was then that England stood triumphant."

Often such views were held by the monuments' subjects too. James Dottin Maycock (1786-1835) whose monument can be found nearby wrote proudly of the British Empire in 1820:

"its power augmenting every day by distant Colonization - and the riches of the most distant countries wafted daily to its shores - it was then that England stood triumphant."

Today we think differently. We understand the human cost of empire and colonisation. We understand that riches were not simply "wafted" to our shores. Rather, that indigenous people were enslaved to produce them. The stories told in this exhibition tell the human cost of the British Empire, revealing what is behind the text of the Abbey's monuments that either praise the empire or are silent about it.

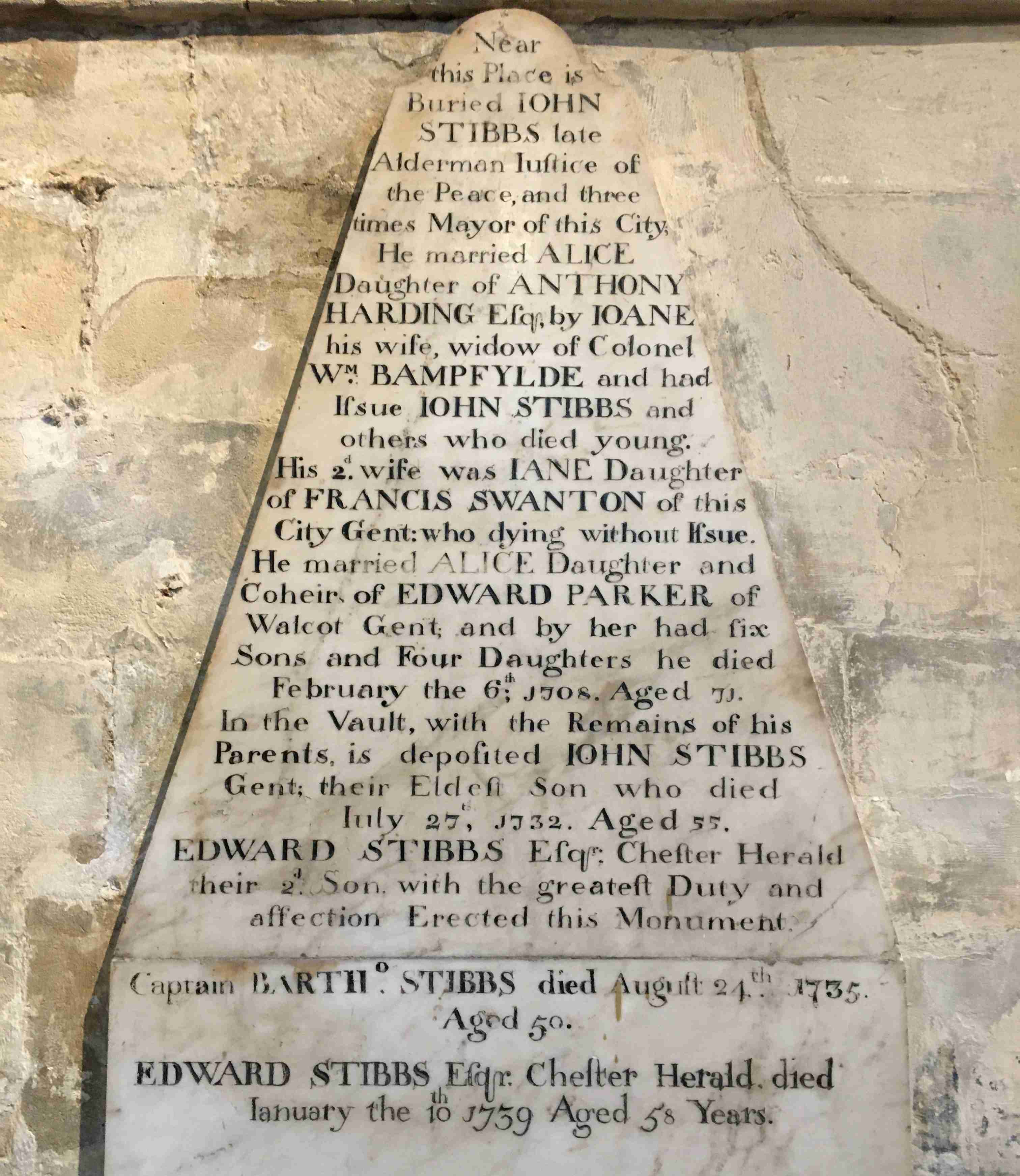

Captain Bartholomew Stibbs: Voyage up the Gambia 1723

Between 1668-1731, the Royal African Company (RAC) trafficked around 186,000 enslaved people from Africa to America, around 38,000 of whom died during the voyage.

Bartholomew Stibbs (1685-1735) was the son of John Stibbs, a pub-owner and three-times Mayor of Bath. He is commemorated on his family's monument on the west wall of the North Transept. Stibbs left Bath for London and became Master of his own ship, the Cornwall Galley. In 1723, he was well-known enough to be asked by the Royal African Company (RAC) to lead a voyage up the River Gambia in West Africa to find gold.

A journal kept by Stibbs during his voyage reveals a small part of the RAC's major role in the transatlantic slave trade. On his arrival at James Island (now Kunta Kinteh Island), a staging post for the RAC's business in The Gambia, he saw almost 400 enslaved people being held before being shipped to Jamaica.

About a quarter of the island was used for keeping enslaved people captive. Stibbs travelled 500 miles from James Island. He never found the gold he was looking for there.

Captain Bartholomew Stibbs and the Slave Trade

Many of the enslaved people Stibbs saw at James Island were trafficked to Jamaica or Carolina. They were bought for 20-30 “iron barrs” each. Stibbs’ search for gold was ended by the RAC because his boat was needed for the slave trade. The new Governor of James Island recalled him and his party returned with 31 enslaved people. Stibbs was personally responsible for buying three enslaved people.

Stibbs went to The Gambia as a mariner and explorer, not to be involved in the slave trade. His journal shows he never wanted to take part in slave trading, but he did so out of a duty to his employer. Like many other sailors and soldiers commemorated in the Abbey, Stibbs furthered and protected the interests of the British Empire at the cost of his personal sense of morality and the cost of indigenous peoples’ lives.

About 1/5 enslaved people died during the voyage from Africa to America in the Royal African Company (RAC) ship.

In 1723, the year Stibbs observed hundreds of enslaved Africans in The Gambia, the profit made on the sale of 2,100 enslaved Africans in Jamaica by the Royal African Company was £5,294 (about £615,000 today). Each enslaved person was sold for £21–£27 “in West India money” in 1723 (about £1,626–£2,090 in today’s money).

Empire, Slavery, and Bath in the 1700s and 1800s

Bath was a fashionable tourist resort that benefited from being close to the port of Bristol: tea, coffee, sugar, spices, chocolate, and other luxuries were brought to Britain from its colonies. The Abbey’s monuments show the mix of soldiers, sailors, merchants, civil servants, their wives and children, from across the British Empire, who spent the end of their lives in Bath. Many brought Black enslaved people with them to the city as servants.

“MARCH 14, 1769. RAN away on WEDNESDAY Night last, From his Master PATRICK BURK, Esq; A Young Negro Man, called Jeremiah or Jerry […] he reads and writes badly, plays pretty well on the Violin, and can shave and dress a Wig […] As the said Negro knows his Master’s Affection for him, if he will immediately return he will be forgiven; if Freedom be what he wishes for, he shall have it with reasonable Wages; if he neglects this present forgiving Disposition in his Master, he may be assured that more effectual Measures will be taken. He has been pretty much at Bath, and the Hot-Wells, Bristol, with his Master.”

Baptisms

The Abbey’s registers record a number of Baptisms of Black people, mostly servants, in the 1700s.

“September 9 1677 One called Bette Gascoin of Bridge Town in Barbados, of about the age of 18 or 19, a black, was baptised ffrances Gascoin”

On 28 September 1754, “William Bath, a Black boy, about 12 years, belonging to Mrs Hetling” was baptised in the Abbey.

Empire, Slavery, and Bath in the 1700 and 1800s

Between 1551–1825, it is estimated that Great Britain alone was responsible for trafficking over 3.2 million enslaved people.

Those in charge of Bath wanted to maintain the city as an attractive destination for wealthy visitors. In 1792, the Bath Corporation refused abolitionists the use of the Guildhall for their meetings six times between March and April. Nonetheless, in March of that year, a petition for the abolition of slavery was made available for the public to sign. One Bath resident, who gave his name as “PHILO-AFRICANUS”, wrote the following reasons for signing it:

"the Slave Trade […] is not founded upon any of those established principles of honourable commerce, by which the trade of this country in general is regulated […] it becomes difficult to say what refinement in treachery, cruelty, and injustice, forms its most prominent features”

Abolition in Bath

In 1807, Britain outlawed the international slave trade, but not slavery itself. In 1825, the “Bath Auxiliary Anti-Slavery Society” was formed. The Society resolved that “the state of Slavery” was “repugnant to justice, humanity, sound policy, & the divine principles of Christianity” and that it would work to abolish slavery in the British Empire.

In 1830, the city’s petition to parliament to abolish slavery had “upwards of two thousand” signatures. However, 2,000 signatures out of a population of just over 50,000 perhaps suggests the apathy of the “the polite city of Bath” towards abolition. The Slavery Abolition Act was finally passed in 1833.

The Alleyne family

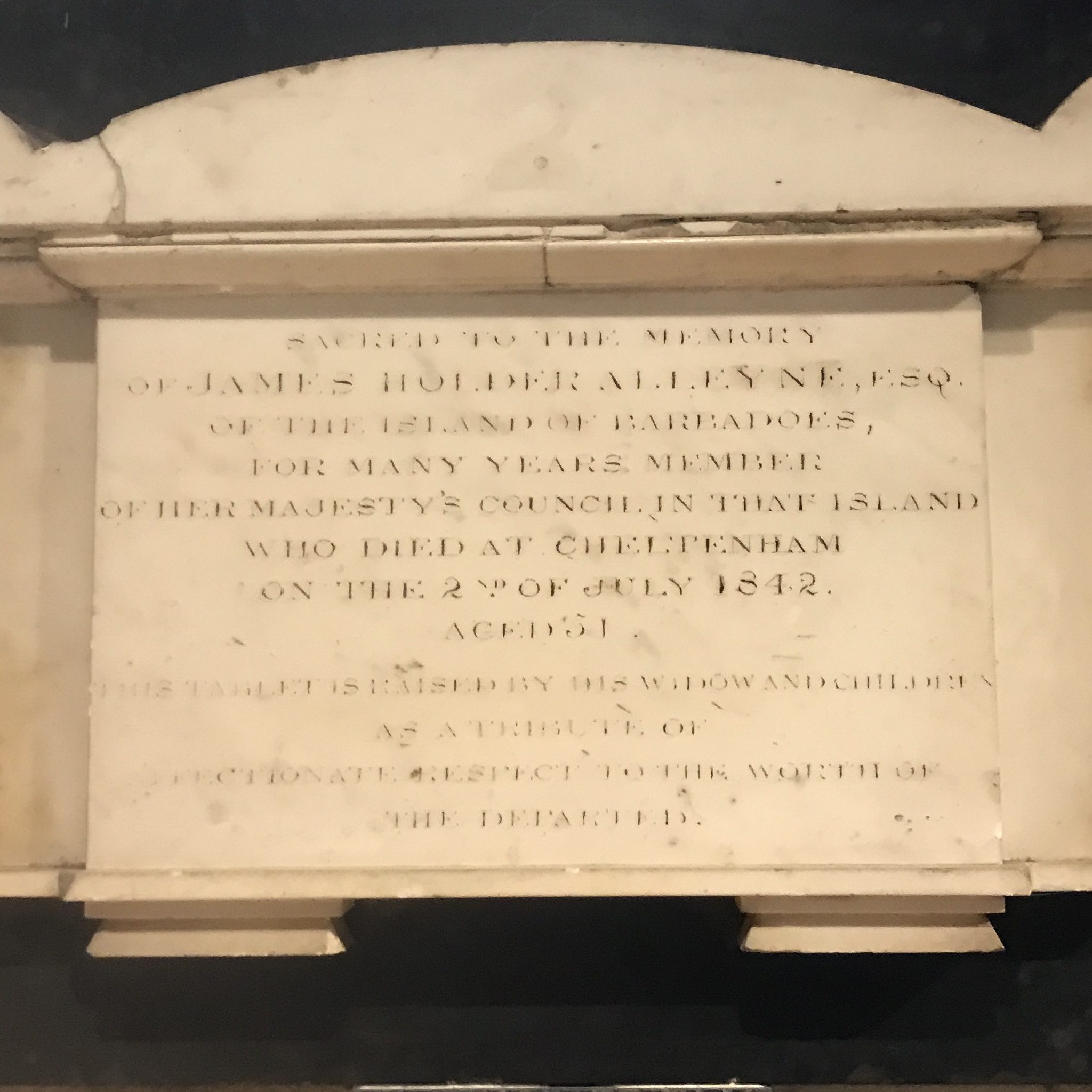

On the north wall of the North Transept you will find a monument to James Holder Alleyne (1790–1842). The Abbey has a number of monuments to members of the Alleyne family. They owned land in Barbados from 1638 and intermarried with other planter families to become both wealthy and powerful. Such wealth was as a direct result of the family’s use of land, connections, and enslaved people.

"While James Holder Alleyne’s relative, Sir John Gay Alleyne (1724–1801), disapproved of the “unhappy sight” of slavery, which he said “leaves an immense debt upon us”, he also owned hundreds of enslaved people. James Holder Alleyne owned six estates on which 739 people were enslaved."

Barbados, sugar, and Bath

About 387,000 enslaved Africans were shipped to Barbados between 1627-1807.

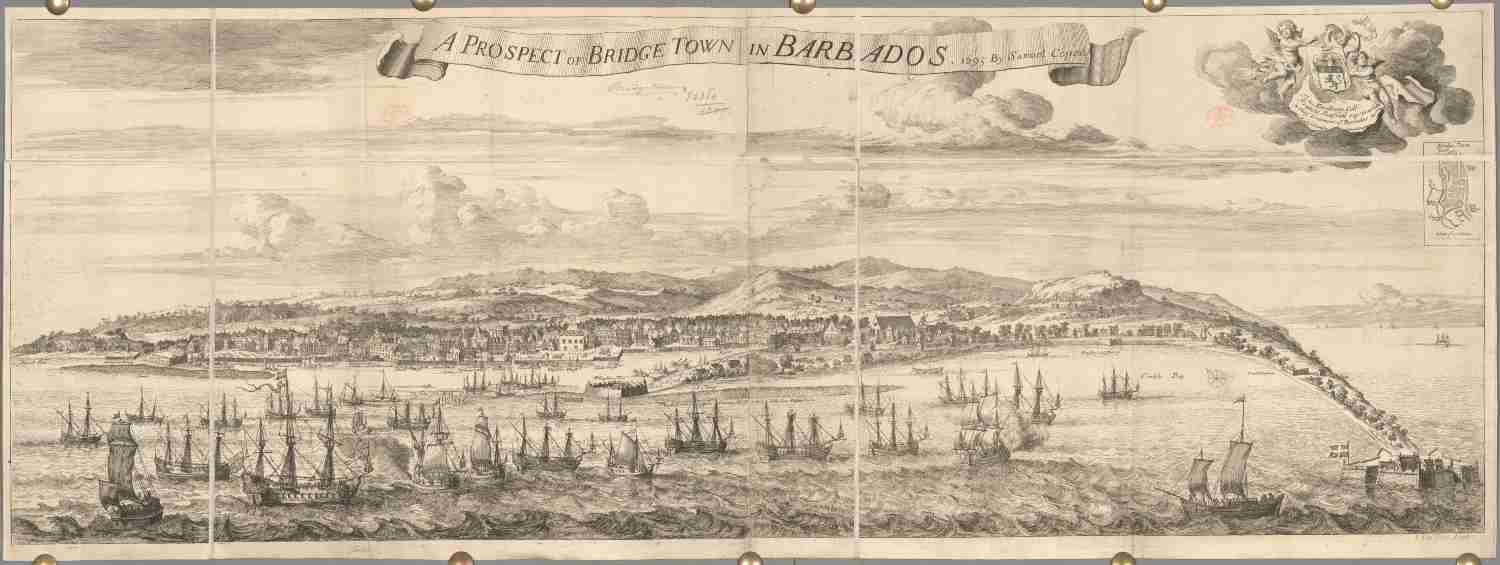

There are 72 monuments with a connection to the West Indies in Bath Abbey, more than any other part of the British Empire. Of these, 25 relate to the island of Barbados. The British settled in Barbados in 1627. The colony first produced tobacco before changing to sugar between 1640–50. This “sugar revolution” led to the almost total deforestation of the island.

Bath residents were directly involved in the sugar industry, from plantation-owners, such as Edward Drax of Queens Parade, to pastry cooks and confectioners, such as John Trinder (Ralph Allen’s cook), who had a shop next to Morgan’s Coffee-House near the Abbey. Enslaved people in Britain’s colonies were worked to death for this industry. The high mortality rate of enslaved people on sugar plantations meant that slave-owners needed a continuous supply of them.

Image: A Prospect of Bridge Town in Barbados 1695. By S Copen. Maps *82380 (1) British Library Board 14/10/2020.James Dottin Maycock 1786-1835

James Dottin Maycock was born in the Parish of St. Michael in south-west Barbados to a well-known planter family. In 1812, he married Sarah Scott Lowe in Walcot parish church, Bath, and returned to Barbados. He was a trustee of two plantations and 311 enslaved people with James Holder Alleyne.

Flora Barbadensis

In 1830, Maycock published Flora Barbadensis, a catalogue of plants in Barbados. It was completed in England after he was “hurried from the island by ill health”. Details in the book reveal the broad and deep impact of colonialism on lands, language, and people.

Once common species like the Mastick Tree, he writes, are “now very rarely to be seen”. While other species, such as “the Bamboo, the Bread-Fruit Tree, the Shaddock, the Hibiscus Rosa-sinensis”, have been introduced to the island from “native soil” elsewhere in the empire.

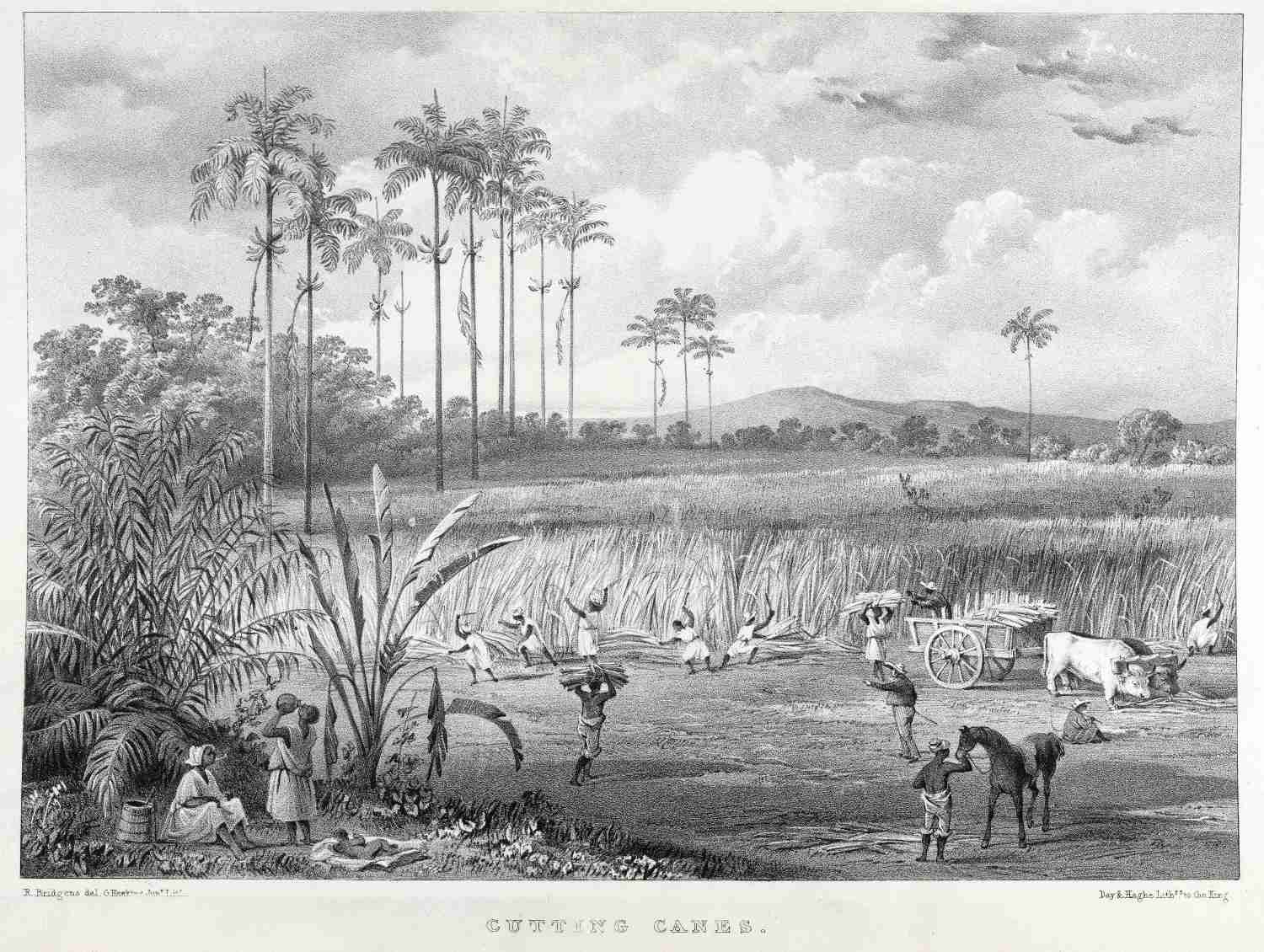

Image: Cutting [Sugar] Canes (18367) 789.g.13, plate 9 British Library Board 14/10/2020.

Sugar production

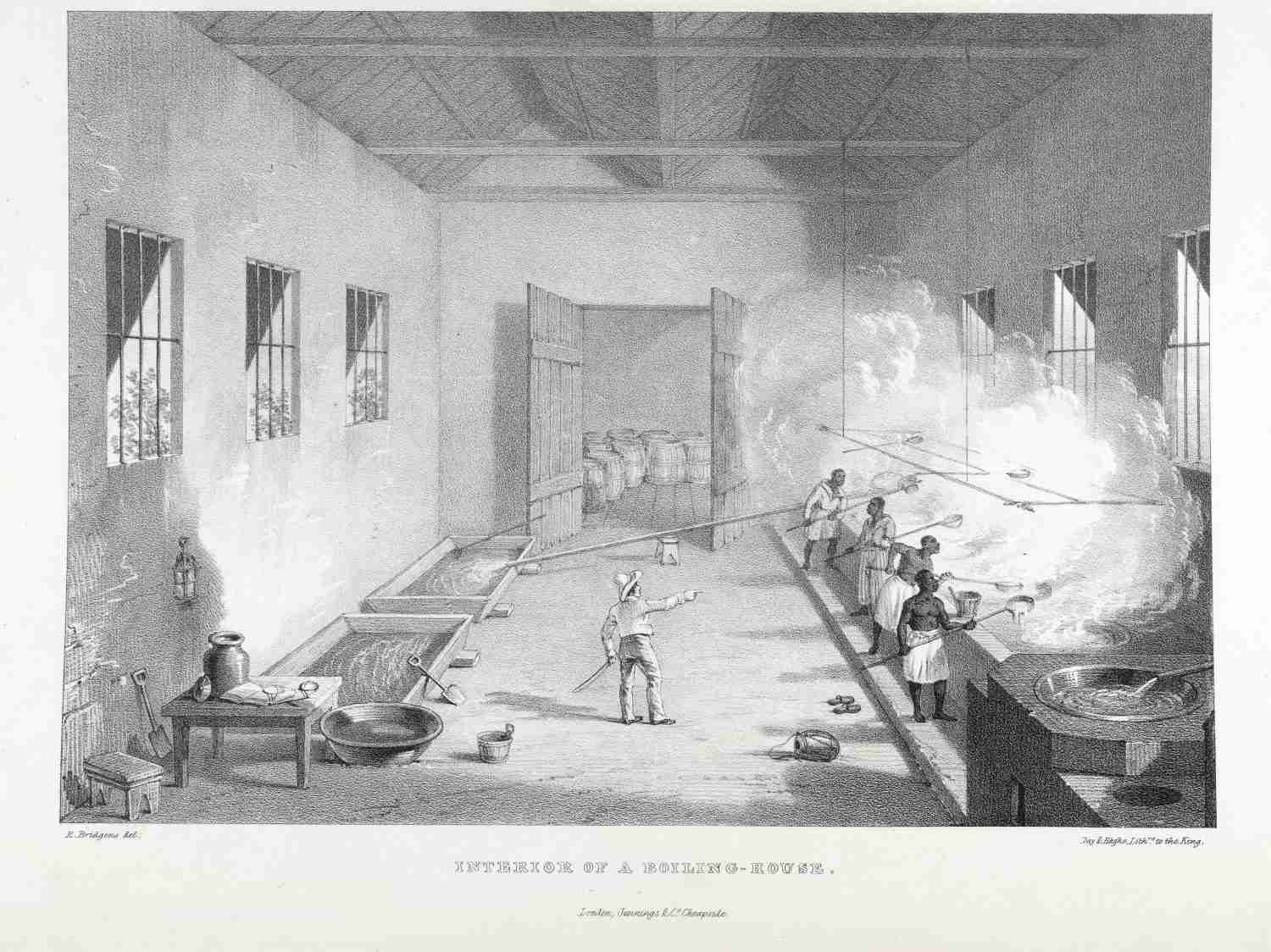

The book also gives an insight into sugar production in Barbados. It describes how clay soil in the north of the island was used in brickmaking. The bricks could last many years even when “subjected to the very strong fires employed in the manufacture of sugar”.

Liquid sugar from sugar canes was piped to Boiling Houses where it was boiled to make crystallised sugar. Enslaved people were used in every part of this process, from brickmaking to producing sugar. Their labour and suffering produced a luxury for European tables.

Image: Interior of a Boiling House (18367) 789.g.13, plate 11 British Library Board 14/10/2020.

The Future

This exhibition is the beginning of a major reinterpretation of our monuments. By working with Black and Asian partners we want to get beneath the surface of what the monuments tell us and share the real stories of the men and women who are remembered here and the untold stories of those who are not.

As a member of Bath’s Ethnic Minority Senior Citizen’s Association (BEMSCA) said, the monuments help us to “look back and think about the past and get others to do that too”. We hope that after looking back we can also look forward to a better future, one where each of us stands up to and speaks out against the injustices of the present.

Responding to this exhibition, another BEMSCA member said:

"it was quite interesting but very sad as after so many years passed it’s coming out now; it should come out long before”.

We agree. The Abbey deeply regrets all past inhumanities, including the evils of the slave trade. We pledge that we will continue to listen to, understand, and challenge issues of injustice and inequality today, and work to create a future where everyone can play their full part in society.

A Prayer to End Racism

Good and Gracious God, who loves and delights in all people, we stand in awe before You, knowing that the spark of life within each person on earth is the spark of Your divine life.

Differences among cultures and races are multicoloured manifestations of Your Light.

May our hearts and minds be open to celebrate similarities and differences among our sisters and brothers.

We place our hopes for racial harmony in our committed action and in Your Presence in our Neighbour. May all peoples live in Peace.

Amen

'Dark Shadows' by Mark De'Lisser

Bath poet Mark De’Lisser has written a new work called ‘Dark Shadows’ in response to the monuments.

Mark describes it as “a poem about acceptance, meeting ourselves where we are and moving forward from that place together. Rather than continually turning away and ignoring the parts of our past that make us uncomfortable or uneasy, I wanted ‘Dark Shadows’ to instead invite the audience to feel that discomfort, to re-examine our history and in turn begin to heal the deep wounds that still affect us today.”

You can watch Mark perform ‘Dark Shadows’ on our Bath Abbey Youtube Channel.